Overhaul & Maintenance

March 19th, 2009

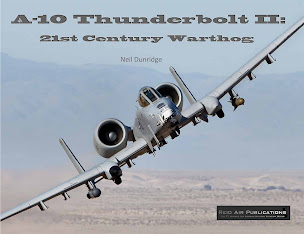

If you have any questions as to the worth of the A-10 Thunderbolt II (a.k.a. Warthog), just ask the soldiers in Wanat, an impossibly mountainous region of Afghanistan. They were fighting for their lives this past July. U.S. Air Force A-10s and other craft flew into a river valley near the place and laid down withering fire, helping hold back the opposition until U.S. troops could evacuate their wounded.

Absent the rugged, "low 'n slow" Hog, what was a very bad day for these men could have turned out far, far worse.

The Hog has been integral to close-air-support missions in Iraq and Afghanistan, but the venerable aircraft (first operationally deployed in March 1976) has begun to show its age.

The problem areas were located on the underside of the wings, in the landing gear area just outboard of where the gear attaches to the wing. "[They're] in the skin," said Lt. Col. Jim Marx, deputy commander of the 538th Aircraft Sustainment Group at Hill Air Force Base, Utah. "It's in what we would describe as the 'aft lower skin' of the wing," said Marx, specifically near the center panels of the landing gear trunnions.

Taking no chances with the welfare of its warfighters, the Air Force originally grounded a full 145 of the 356 A-10s in its active inventory. When this interview was conducted in late January--four to five months into repairs--the number of aircraft whose duty-time was limited had plummeted. "We're down to 55 [aircraft] that are on flight hour limitation," said Lt. Col. Dave Ruth, the A-10's weapon system team chief at Air Combat Command headquarters in Langley, Va.

The A-10s still are flying, and the nature of their missions hasn't changed. They can still get in low 'n slow, still sling armor-piercing shells via their potent 30-mm GAU-8/A Avenger Gatling gun. The Air Force says it didn't want to impose g-loading restrictions on the Hog, didn't want its pilots to second-guess the capabilities of the airplane when things get hot.

What the Air Force did want to do was get as many of the airplanes repaired as quickly as possible and back in the fight. That's imperative, because the 356 aircraft currently in the inventory represent just about half of the 715 Warthogs that have been built. Consider further that as of this writing some 240 of those 356 are actually flying (the rest are in various stages of repair), and the urgency of the challenge is apparent. Despite the advent of newer, sleeker aircraft, none of them possess the close-air-support capabilities of the ineffably ugly A-10.

The Longevity Equation

The cumulative current rigors of Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom today, and Desert Storm two decades ago, have put lots of wear on Warthog airframes. "The high-time airframe is right around 12,000 hrs.," said Master Sgt. Steve Grimes, headquarters Air Combat Command maintenance liaison with the Systems Program Office. "The low-time life is just under 3,000 hrs." On average, Warthogs have racked up around 8,800 flight hrs,, about half the current life expectancy of 16,000 hrs.

Pushing these airplanes through the repair process is imperative. Marx declined to say how much the work will cost, but he does offer an idea of when it will be finished. "We started repairs in the August 2008 timeframe," he said. "We expect that by the summer of 2009 we'll have everything completed."

The Fix

Marx said the repair process--start to finish--takes "several hundred [man]hours to complete." That's because of where the cracks are located. "As you can imagine," he said, "to get to the wing skin in [that] area we have to take a considerable number of panels away, and we have to remove the landing gear and some other structure to get to the wing skin we need to look at."

Getting there is half the fun, but you've got to be small to really enjoy it. In this instance, "it" is the "Hell Hole," a claustrophobically compressed area that offers access to the cracks in question. "It's not a very nice place to be," said Capt. Kristen Shadden, operations officer for the 571st Aircraft Maintenance Squadron at Hill AFB.

But it is the best way to get at the problem.

Through the classic process of continuous improvement, the U.S. Air Force doesn't sequester its successes, doesn't silo maintenance techniques that work best. At Hill, Shadden said maintainers actually were removing the outer wings to get at the work area. Down at the Aircraft Maintenance and Regeneration Group (AMARG) at Davis-Monthan AFB, Ariz., they were going at it via the Hell Hole. It's "just above the landing gear," said Shadden. "You can open up a couple of panels in the wing and just fit in a small human being."

Davis-Monthan is one of four prime sites where the Air Force is executing the fixes. The others are Hill, a location in Europe, and Korean Airlines in the Republic of South Korea.

After talking with their counterparts at Davis-Monthan, Hill maintainers decided to switch approaches. The Hell Hole was in, and wing removal out. In making the change, "We went from 29 workdays to 14," said Shadden.

Access achieved, it's time to make the repair. Preceding all of this, of course, is non-destructive testing, non-destructive inspection. Marx said, "That's going to tell you whether you have a crack, and how significant the cracks are." At that point, the roster of options ranges from reaming the skin to implanting repair plates.

"We NDI with a surface probe," said Hill sheet metal mechanic Dan Wright. "If there's a crack indicated, we continue to grind [it] out until it's totally gone." In this case, the flaw is just skin-deep. "We're not getting into the spar or any other stiffeners or structure," said Wright.

If the crack is a large one, a 6-in. by 14-in. doubler does the deed. "It's meant to relieve stress where the cracking is happening," said Marx, "and better distribute the load as the aircraft continues its mission."

This portion of the process takes 50-60 man-hours, said Wright. That encompasses performing the cutout, drilling the plate, and working with the machine shop to shim up the trunnion, the area at which the main landing gear mount attaches to the belly of the aircraft. "We're running into some trunnion issues," said the sheet metal mechanic. "With the doubler, you're changing the height of the trunnion where you're going to re-attach [the landing gear]. We have to re-shim to get proper height for the landing gear to be aligned properly."

Clearly, this is no cut and paste job. As Marx said, the whole process consumes hundreds of man-hours.

To get it to consume less, the Air Force is milking continuous improvement for all it's worth. Going in through the Hell Hole rather than removing outer wings was the biggest process improvement.

But there are others. Shadden said one of the most effective things was to issue pagers to both supervisory and critical members of the Hill A-10 wing crack team. That did away with a lot of the endemic "hurry-up and wait" nature of running an MRO operation.

"We give them a 30-minute page [as] to when they're going to be needed on the aircraft," said Shadden. The page identifies the tail number "so that they can be [here] as soon as the previous skill is finished working on that aircraft."

Another relatively mundane, but eminently sensible measure was to requisition a dedicated government vehicle to move maintainers between tasks. "We had a lot of mechanics who were basically just beating the pavement, and walking back and forth between different areas to get parts," said Shadden.

"Looking for opportunities to take waste out of the process" can be exactingly site-specific, she indicates. At Hill, "we have people who are in different buildings. There can be movement issues. Other places, like Tinker [Air Force Base] has some co-located efforts. They may not have that problem."

One problem the Air Force sought to short-circuit from the get-go was moving aircraft back and forth between operational areas and rear-echelon depots for maintenance. The idea is to perfuse as much of the fix as possible out into the field, to train--and equip--front-line maintainers to do the job as far forward as feasible. None of these moves is rocket science. But they are anchored in the rock-solid realization that the A-10 is at this precise point-in-time perhaps the indispensable warfighting aircraft out there.

Operational readiness matters for all military flying machines. But if you take a poll among infantrymen on the ground, those who pray for the A-10's ugly silhouette to save the day, you'd be hard-pressed to find a machine that matters more than the Hog.

Photo credit: Billy Arrowood/U.S. Air Force

This article appeared in Overhaul & Maintenance's March 2009 issue.

Source

I was going to post or recommend a link to http://aviationweek.com/aw/generic/story_generic.jsp?channel=om&id=news/omA10309.xml&headline=Reworking%20The%20A-10%20Wing at aviationweek.com but I see you already have it covered (I should have known)! Next time I'll remember to come here first.

ReplyDelete